On a dive outing at a local quarry a group of Open Water students are enjoying their checkout dives. At the end of dive number two a student diver surfaces saying she’s lost her buddy and he has not surfaced. While quickly scanning the surface for bubbles, the instructor and DM get all the students to shore and sound an alarm. Those on shore take action by notifying the quarry owner, calling EMS, and gathering information from other divers coming out of the water. The instructor and his assistant search in the last reported area the diver was seen. It is near an underwater platform used for training. They spot a fin tip sticking out from around the corner or the platform. It is the missing diver – a 60 yr old man, eyes wide open, and with his regulator out of his mouth. They bring him to the surface and begin with in water rescue breathing followed by CPR once they reached shore but it is too late. The diver never regains a pulse and is taken away by EMS personnel.

An autopsy will show that the man suffered a massive heart attack from a previously unknown condition. Yet the assistant cannot get the man’s face out of his mind. Underwater, no regulator, eyes open, but lifeless and staring straight ahead. Mixed with that is the woman’s accusing voice that haunts him. He has difficulty sleeping, withdraws from his friends, and though he still dives, he no longer will assist with classes. The instructor suddenly cancels all classes and ignores his other students’ calls and emails. He is cleared of criminal wrongdoing. Following this, he drifts out of the local dive scene and moves away with no forwarding address.

A group of friends is having a good time at a local lake. One member of the group had previously been involved in the rescue of a diver a couple months earlier that did not turn out well. Yet until this time he had not been suffering from any after effects of that incident. Suddenly one of his friends suffers a severe leg cramp and yells for help. Others rush to his aid and pull him from the water. He suffers no serious injury and soon recovers with some stretching and massage of the leg muscles. Another diver looks at the one who had been in involved in the previous rescue and asks why he did not respond as he was so close.

The diver says nothing and turns away from the group, packs up his gear, and speeds from the site. A few days later he brings his gear to the local shop and asks them to sell it. He refuses to take calls, does not answer emails, and is heard to be having problems at his job. Yet he will talk to no one and is about to be fired when his boss sends him to an employee intervention program. Here he discovers that his first rescue experience, that did not turn out well, caused him to not respond to a rather simple need for assistance. The guilt he felt over that, as well as subconsciously feeling he could have done more in the first scenario and perhaps changed it to a more favorable outcome, turned into something serious that affected his entire life. With the help of a trained professional he was able to come to terms with these events but he never dived again

During a series of OW dives a group of divers using rental gear suddenly has a regulator begin to free flow towards the end of the dive; that quickly empties his tank of his remaining air. The diver signals an OOA to his buddy and the buddy donates his octo. As the diver with the free flow takes the octo the cover falls off and he is left holding an octo that does not work. He heads for the surface while continuously exhaling. His buddy follows and soon surfaces beside him. He is congratulated for executing a successful self rescue. The buddy apologizes profusely and is told that it really wasn’t his fault but that of the crappy rental gear. They laugh it off and decide to end the diving for the day and both seem fine.

That night, the diver whose reg fell apart catches himself analyzing the incident until he realizes that he is up much later than he should be. He sleeps fitfully and has rough day at work. It happens again two days later. The diver with the free flow finds that on the next dive outing that he spends much of the first dive tense and preoccupied with his air supply, to the extent that he loses track of his buddy and has to swim hard to catch him. The next dive is not much better. He enjoys neither of the dives. The next weekend he bugs off one of the days and soon finds that he is not interested in going at all.

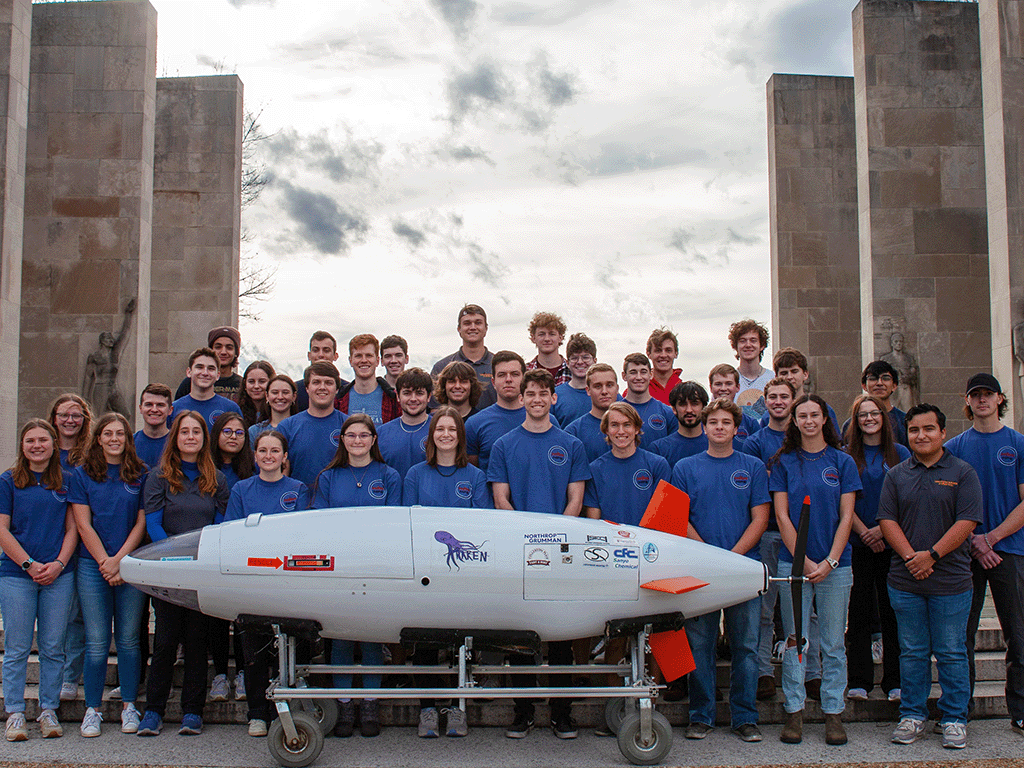

Rescue Diver Course - Image Courtesy of Ocean Quest Dive Center

These scenarios are fictitious and are not taken from any one actual event but parts of many that did actually happen. The reactions of the individuals involved are, in some cases, true. Others are compilations of reported effects. All of them are used to illustrate the effects that Simple Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder or Simple PTSD may have on a diver who rescues another.

The idea for this addition to a Rescue Diver course is the result of having been involved in rescues of recreational divers. Speaking with other divers who were able to be of assistance to one of their own contributed to it. It is from reading the reactions of divers to events that did not turn out well and the effect the incident had on them and others involved with the rescues. It is based on related experiences with the survivors of the victims. Note that for this article the victims include the rescuers.

Not all rescues will have positive outcomes. Even those that do may have effects that the rescuers may not see coming. Those effects may present themselves to varying degrees over different lengths of time. When they do, they need to be addressed. How they are dealt with depends on the severity of them and the individuals experiencing them.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder - PTSD - is a very real possibility for those who have just been involved with a life or death situation in a recreational dive setting. Those accidents that only involved injury to a diver’s ego may also have lasting effects on them and others.

SCUBA diving is an activity that for many people is filled with adventure, knowledge, and enjoyment. It is an activity that is safe as long as one follows their training and experience. Pushing those limits too far, too fast can result in an accident. One that can have devastating physical effects and may result in death. Even when all the rules are followed changing dive conditions, weather, currents, tides, and even marine animals may cause injury to a diver necessitating a rescue.

A previously unknown medical condition may also cause a diver to require assistance. Another possible cause of a distress may be from becoming entangled in fishing line or kelp. Careless boaters may also result in injured divers. In some cases, it is the diver themselves, through error or carelessness, who will put their safety and life in danger.

Regardless of the cause, the diver will require assistance; perhaps life saving assistance. You, the rescue diver (any diver really), are likely to be the one looked to for that assistance. A Rescue course is arguably the most important course you can take after Open Water. Some agencies require you to also have advanced training before the Rescue course along with a minimum number of dives. Others only require Open Water and 10 dives. The critical idea is to recognize the importance of having the ability to provide assistance to another diver and to prevent issues from turning into accidents.

Some of the skills in a formal Rescue course are also taught in OW classes offered by some agencies. Divers not taught under such a system may not have had any rescue skills other than a tired diver tow or cramp removal. If the only problem a new diver could be expected to encounter is a tired diver I, for one, would be extremely happy. Reality is far from that ideal. What we are concerned with here is dealing with the effects of the need to rescue a diver that may be felt after the incident by those who provide that assistance.

The rescue/recovery of a human being is a profound experience. Ask any firefighter, police officer, or EMT. Any of them will tell you honestly that each rescue has an effect on them. That even though they may have performed thousands of them, one may be the one that has affected them for a long time. Military personnel who have seen the effects of combat and had to pull buddies and parts of buddies out of that hell are most often cited as likely to experience PTSD.

It was first in these members of our armed forces that PTSD was diagnosed and described. Previously it was called Battle Fatigue, Shell Shock, or some other term. Soon psychiatrists, psychologists, and therapists began to see the exact same signs and symptoms in patients who had never experienced combat or saw the effects of it. What they realized was that these people were experiencing the same effects as a result of having been involved in traumatic events or, in some cases, from witnessing these events.

Whatever the cause, the end result can be summed up by saying that anyone involved in a serious rescue scenario with a fellow diver stands a chance of being mentally injured by that scenario.

PTSD is sometimes referred to as a Mental Injury.

This is different than a mental illness. It is also nothing to be ashamed of or hidden from everyone. It is a treatable condition that affected 8 million Americans in 2006 according to the National Institute of Mental Health.

What we are talking about here is not the same type of PTSD that is manifested in those who are exposed to mental trauma day in and day out. What we are talking about here is the PTSD that is brought on by a single event. Known as Simple PTSD; it is a reaction of the subconscious mind to a single violent or frightening event. For our purposes this single event is a diving accident. It need not be a fatality or even life-threatening event to shock the system and produce signs and symptoms of PTSD. Even an event with a successful outcome can have long lasting effects. So, what are the signs and symptoms that someone may be experiencing this?

Rescue Diver Course - Image Courtesy of Ocean Quest Dive Center

Signs and Symptoms of PTSD

A frequent sign of PTSD is repetitively thinking about the event. These thoughts may suddenly come into your mind even when you don’t want them to. They may come in the form of nightmares or flashbacks about the event. These flashbacks can result in inflated reactions at inconvenient times. You may get upset simply by being reminded of what happened. You may react when you see a picture of the place it occurred. You may also experience these episodes in small snippets of the event. You may see the face of the victim or others who were there. All of these have the potential to occur at any time. In the period immediately after the event these are normal occurrences. When they persist and interfere with daily life they need to be addressed.

Another common sign of PTSD is hyper-vigilance. Hyper-vigilance is brought on by a mental injury. It is a state of heightened alertness. A person suffering from PTSD is often like this constantly. They are not able to relax and the smallest disturbance can create an overblown reaction. This hyper-vigilance may also result in a sense that you are somehow less than worthy of other’s attention and consideration. This may lead to depression. It may also lead to dangerous situations due to an overreaction to a stimulus. Driving a vehicle is a good example of a potentially dangerous situation. One should always be attentive and responsive when driving. Taking evasive action as if one were avoiding combat is usually not necessary in a quiet neighborhood.

Insomnia may become a frequent complaint. This may be a result of seeing the event when you close your eyes, the hyper-vigilance, or for a reason that you simply cannot identify. All you know is that it’s 2 AM, you’re exhausted physically, yet your mind simply will not shut down. You may be able to sleep for several nights in a row thinking that you have it controlled; only to spend the next several nights desperate for sleep. In some cases, medication may help; but only for a short time. Using medication for extended periods to deal with this presents its own issues of possible dependency. Another common complaint is that while you sleep for what should be a sufficient period of time, you wake feeling run down and lacking energy.

You may find yourself going to great lengths to avoid things that remind you of the event; locations, people and perhaps even the activity itself in extreme cases. Some people involved in the rescue of a diver that did not have a good outcome may go so far as to stop diving. This may or may not be an extreme response. If the events are so traumatic and upsetting that recalling them detracts from the dive planning process so that diving itself now becomes unsafe due to inattention to detail, then perhaps it is for the best that the diver stops diving. If you are an instructor you may find that the idea of teaching now becomes a source of anxiety rather than enjoyment.

Rescue Diver Course - Image Courtesy of Eco Dive Center

Panic attacks can also manifest themselves. These appear as a feeling of intense fear accompanied by shortness of breath, dizziness, sweating, nausea, and a racing heart. Some mistake panic attacks as heart attacks as they may also be accompanied by tightness or burning in the chest. Not all of these symptoms will occur at the same time but any of them could at any time. While not as severe as a panic attack, being in a similar situation may result in a feeling of being unable to breathe that could escalate into an attack.

If you are able to recognize this occurring, stopping whatever you are doing, closing your eyes, thinking of a calm setting or relaxing image, and breathing deeply and slowly may help. Another valuable technique is to assess your current location. Look around, observe the area, focus on a few items and decide if these would truly occur in the location where you experienced the event. In the case of an accident that has occurred underwater, it’s pretty easy to realize that a moving bus is not going to be there and help bring you back to a safe place.

You may also experience feelings of mistrust. These feelings may be towards strangers, friends, family, or the world in general. This can result of feelings of loneliness and isolation. You may look at the world itself as something to be feared. This may result in errors in judgment or being overly cautious to the point of inaction.

Unexplained chronic fatigue is another possible sign that something may be wrong. In fact the body needing to fight the other symptoms may in itself contribute to the feeling of fatigue. It takes a great deal of energy to maintain a hyper-vigilant state. Not being able to rest or sleep only adds to that. The panic attacks also use up valuable energy.

Another possible sign of trouble is a sense of guilt or responsibility towards others who may have been affected by the event. You may see yourself as somehow responsible or not having done enough. This may lead to you stretching yourself thin to the point of causing further harm to your own mental, physical, and emotional health. A third party that knows you can be an invaluable source of support and see when you are endangering your own recovery.

Dive professionals associated with the dive can be especially at risk here. They may feel that this occurred “on their watch” and while nothing they did could have prevented the event they still may feel the need to make up for something. It may affect how and whether they will ever teach again. If they do decide to take on the role of educator again it should be done slowly.

Everyone is different and will react differently. BUT there is a huge difference in the theoretical vs the real-life experience of someone who has been through this. It affects your whole life in ways you may not be able to see or even imagine until you stop, take moment, and look at how you are thinking, acting, reacting, and perhaps overreacting.

Those who have not experienced this really have no idea how it feels and while support is appreciated one thing to avoid saying is "I know how you must feel." Because you don't. An injury or death where a student is involved is like nothing you've ever experienced. Especially when it's "on your watch."

Everyone knows and says it wasn't your fault. They know you did everything you could and gave them the best possible chance. You may be able to accept that in your head fairly quickly (a few weeks, month’s maybe). It's in your heart that can take a long time.

Why? Because you care. You care about your students and other divers. It is now tough to see training taken lightly. When this is not given the respect, it deserves. When you have seen firsthand how quick life can be completely turned upside down in every possible way in a few seconds or feet and it seems that others don't get that.

Those are the feelings you need to be aware of that can cause you to overreact, react too fast, too slow, or not at all. So, we need to be sure we are ready before getting back in the water with new divers. That may take a little time and require the help and support of others we trust and can rely on.

I can tell you that you will never look at a medical clearance form the same way.

You will never look at a student or dive buddy who is looking a little under the weather, out of breath, out of shape, or just doesn't seem themselves the same way ever again.

You will find yourself going over things more than before. Maybe obsessively so. Be wary of that.

You will definitely look at life in a whole new way.

There may be other subtle signs. All of us at times go through periods where we are easily distracted, lose our train of thought, or get irritated at small things. The difference though with PTSD is that these small things can be nearly constant or such that they interfere with simple daily living.

Further indicators may need to be diagnosed by a professional.

Help with PTSD should also be sought from a person with specific training in the diagnosis and treatment of PTSD

Rescue Diver Course - Image Courtesy of Eco Dive Center

Finding a therapist, psychologist, or psychiatrist who specializes in PTSD can be done via a number of routes. One of the first avenues to consider in locating treatment may be consulting your family physician and asking for a referral. Another possible source may be a member of the clergy. Your community mental health agency or local hospital may also have information to aid you in seeking treatment. If you have health insurance through some source such as an employer they may have a referral service.

Be sure to insist on a referral to a provider that specifically deals with the subject

Some may refer you to those who have little or even no training and experience in the field. While they may actually be very good in other areas and very nice people that want to help, not all have actual formal training and experience in the field. You may need to go “out of network” to find a provider. That may mean extra costs. To get help from the right person, however, it can be well worth it. Some work on a sliding scale and are able and willing to work with their clients to see they get the help they need. Don’t be afraid to ask!

Dealing with PTSD

As previously mentioned dealing with PTSD requires the expertise of a professional trained to diagnose and treat the disorder. Not all therapists, psychologists, and psychiatrists specialize in dealing with PTSD. Not every person will respond to one specific treatment. This is why there are different methods used to address it.

When to get help is another consideration. If any of these symptoms interferes with your daily life that is a good indication that you need to consider getting help. Some people may require help immediately after the event. If this is the case all a family member or friend may be able to do is be supportive of the person and, if necessary, help them make arrangements for treatment. Try to find a trained therapist to work with you on an individual basis and then follow their recommendations for treatment.

Some things you can do for yourself to help with the treatment that they may recommend are simple and can be done in conjunction with your treatment plan. They include but are not limited to the following items:

- Stay close to your family. They are ones that will be close to you for the duration.

- Don’t alienate your friends. They can at times be easier to talk to than family.

- Do things that help you to relax and calm your mind and body.

- If you have never tried it, meditation can be extremely helpful. Some types are best done under supervision and with a little formal training by an experienced practitioner or professional.

- Though it may be difficult, try to rest and get sleep when you need it.

- Do something physical that you enjoy. Exercise helps the mind as well as the body. Walking for most is easy and can be done most anywhere.

- Stay away from any drugs not prescribed for you and stay away from the alcohol.

- Watch your coffee, or any other source of caffeine, intake. It may stimulate your anxiety and keep you from sleeping.

- Journaling is an often-used technique to reduce stress and help you sort out your thoughts. It may also help your therapist in your treatment.

- You can monitor your own reactions to different stimulus. You know what is normal for you. Abnormal reactions should be noted and discussed with someone you trust.

- Be prepared to not be yourself for a few days or even a couple weeks. Allow yourself time to recover and see things clearly.

- Listen to those who are able to see the situation objectively. They may help you to see that you did everything you could.

Your therapist may suggest other things to help in your recovery. Trust them and follow their advice. Finally, do not forget that this condition may take time to deal with.

During that time don’t lose sight of the reality that you can get better. There is a light at the end of the tunnel and you are not crazy or mentally ill. You are injured and injuries take time to heal, but they do heal.

Maybe not as fast as we’d like, but with patience and the right help you will be back to some semblance of your normal self. This is not to say that it will be 100% better. Injuries leave scars – some more visible than others. But scars sometimes make us stronger and enable us to handle issues with a little more knowledge and wisdom. They also may enable us to help and relate to others who may go through similar issues in the future.

References

Mental Health America: Post Traumatic Stress Disorder- PTSD ©2011 Mental Health America / formerly known as the National Mental Health Association www.nmha.org

Guy Lewis, Payson, Arizona, Thursday, May 27, 2010, PTSD is Mental Injury not Mental Illness, on http://sobern90.wordpress.com/2010/05/27/ptsd-is-mental-injury-not-mental-illness/

Bryan E. Bledsoe, DO, FACEP, EMT-P, EMS Myth #3: Critical Incident Stress Management (CISM) is effective in managing EMS-related stress, on www.emsworld.com/article/article.jsp?id=2026

A. W. Rousseau, M.D., FAPA, American Psychiatric Association, Disaster Psychiatry Handbook, on www.psych.org/Resources/DisasterPsychiatry/APADisasterPsychiatryResources/DisasterPsychiatryHandbook.aspx

In addition I would like to thank Elizabeth Babcock, MSW, LCSW for her invaluable assistance, guidance, and advice.

---

Written by James Lapenta

Jim Lapenta is an Instructor holding the following ratings:

SEI Instructor, CMAS 2 Star Instructor, SDI Instructor, TDI Instructor.

He is the author of two books –

SCUBA: A Practical Guide for the New Diver,

SCUBA: A Practical Guide to Advanced Level Training.

He is also the author of the SDI Drysuit Course and an editor and technical contributor to the SDI/TDI Sidemount Course and ERDI Full Face Mask Course.

In 2013 and 2016 he was nominated for the DAN Rolex Diver Award for contributions to diver safety.